Article Index

DEATH OF FOUR SNOWBOARDERS IN A SNOW CAVE

The relevance of this event to Australia's Ski Heritage is that it is a sad demonstration of the value of huts above the snowline, not only from the aspect of providing safe shelter, but also their value in simplifying the location of overdue cross-country travelers in the snowfields. Unfortunately, snow caves and tents can become death traps if heavy snowfalls occur and/or large snowdrifts develop in windy conditions overnight.

On Saturday morning 7 August 1999, four adult male snowboarders carrying heavy packs departed the top station of the Thredbo chairlift bound for the area between the Racecourse Gully and Lake Albina, a distance of 10km, where they planned to dig a snow cave and snowboard the nearby slopes. They had left a map, on which their planned route was marked, plus their planned schedule, with a close relative, who was asked to phone the Jindabyne police should they have not returned by Monday night 9 August.

The weather forecast issued at 5.30am for that Saturday, was for a fine and mostly sunny day with moderate to fresh northerly winds and nil probability of snow overnight. The forecast did warn of deteriorating weather from Sunday into Monday. However, the storm developed soon after the four snowboarders had left Thredbo and by midnight Saturday night, the Kosciuszko Main Range was subjected to gale force winds and driving snow.

A group of scouts and adult leaders had camped that day about mid-way between Thredbo and Mt. Kosciuszko, just over a kilometer from the snowboarders, but unaware of the snowboarders' presence. One of the leaders of the scout group had pitched a tent whilst the others excavated a snow cave.

After their evening meal the scouts had retired to their sleeping quarters. The tent occupant awoke just after midnight to find his tent buried under masses of drifting snow. After clearing snow from around the tent's entrance, he went over to the snow cave and unblocked its entrance, so as to maintain the air flow to its occupants. It was snowing so heavily that he had to repeat this clearing of the tent and snow cave entrances two more times during the night.

When the four snowboarders had not returned to Thredbo by 9pm Monday, the Jindabyne Police were contacted. The Police verified that the snowboarders' car was still parked at Thredbo and, after an overnight check of the local bars, hotels and lodges in Thredbo, a full search commenced at 7am Tuesday morning. The search continued every day for nearly three weeks and found no trace of the missing men, despite covering 300 square kilometers and involving up to forty searchers with oversnow vehicles and aircraft.

The possibility that they had been buried under a massive cornice avalanche that had occurred off the south-eastern slopes of the Kosciuszko Summit Ridge was tested by digging with large machines. Special airborne thermal sensing gear found no trace of human warmth in the bush or under the snow.

By the end of August the reluctant conclusion was drawn that the missing four men were deceased. Occasional air searches were carried out during the Spring thaw. On Tuesday 16 November, the crew of a naval helicopter spotted a black hole in the side of a snowdrift and landed to investigate. Ski poles were protruding through the snow beside the black hole, which was the entrance to a snow cave. The bodies of all four missing men were found inside the snow cave, which had not collapsed. A stove had been used but autopsies showed that carbon monoxide poisoning had not occurred. No blood alcohol was detected in any of the four deceased men. The pathology report concluded the four deaths were the result of accidental suffocation, possibly combined with hypothermia in two of the four cases.

John Abernathy (NSW Coroner) commented, "I can only say that it would be prudent for snow cavers to always ensure that some type of aperture to the open air is kept, even if this means maintaining a 'watch' throughout the night."

Dr Peter Hackett, then President of the International Society for Mountain Medicine, quoted a 2001 disaster in Nepal when the dean of the Washington University medical school, his family and all their Sherpas were suffocated in their tents. "They suffocated in a huge snow storm that buried their tents. No avalanche, just heavy snow". Dr Hackett also drew attention to the significant risk of carbon monoxide poisoning in tents and snow caves from using camping stoves. The obvious conclusion is that mountain huts are much safer places than snow caves and tents (particularly those tents made entirely of water-proofed, impervious fabric).

SEARCH IMPLICATIONS – TENTS AND SNOW CAVES

One of the most concerning aspects of the suffocation of the four snowboarders in their snow cave, is the virtual impossibility of finding snow caves and tents that have been buried under the snow, unless their locations are already known to an accuracy of better than +/- 100 metres.

Sergeant Warren Denham of Jindabyne police, who was the field leader of the search for the four snowboarders, is very certain that he and other teams passed directly over the site, or very close by, several times during the first few days of the search. So much snow must have accumulated that all sign of the snow cave was buried, including the ski poles standing alongside its entrance.

Mountain huts containing logbooks, in which all parties record their travels, are the best means of minimizing the size of the area to be searched in order to locate a missing person or a missing group.

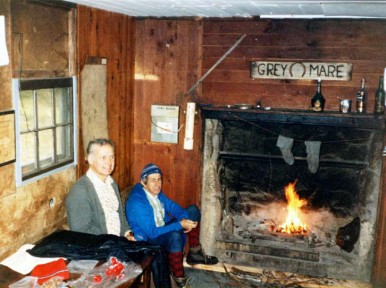

Two invaluable survival-enhancing features can be seen in Photo No. 46, taken in 1987 in the Grey Mare Hut in the Kosciuszko National Park: -

Firstly there is a fire burning in the fireplace to dry wet clothing (with supplies of dry firewood stored in a "lean-to" against one external wall of the hut) and, secondly, a logbook can be seen prominently displayed on the wall to the left of the mantelpiece. During any search in this area, the logbook would be the first thing to be consulted by searchers, should the missing skiers/hikers be not physically present in the hut when the search party arrived.

There also is a map mounted on the wall beside the window, should a touring group have accidentally damaged, or lost, their map of the area.

Even basic cattlemen's huts, like Horsehair Hut (Photo No. 47), provide shelter from the elements, plus a fireplace and the opportunity to dry wet clothing and equipment.