Article Index

THE ALPS AT THE CROSSROADS

The threat to all shelter huts within the Kosciuszko National Park had become apparent in early 1966 following the sending to the AAC of a letter of intent by the Kosciuszko State Park Trust (KSPT) to compulsorily acquire the AAC's Lake Albina lodge. The "Sydney Morning Herald" of 28 May 1966 published an opinion piece on the apparent desire of conservationists within the KSPT to remove alpine shelter huts, under the heading "Ski tourers versus conservationists". After noting the magnificent skiing available to ski tourers on the Kosciuszko Main Range, the article drew attention to the potential hazards. "It is also a dangerous world, where a blinding mist can come down in minutes and often freezing winds, unbroken by any intervening mountain chain, blow from the Antarctic with devastating force. It is not a place for the foolhardy, the unfit or the inexperienced." The ski tourers would like "a chain of simple, non-commercial touring huts similar to Albina on the Main Range, making possible easy ski-touring of the area with overnight stops, as is the practice in Europe. .....Under the present provisions of the master plan, however, such a project seems unlikely to be permitted."

The Victorian National Parks Association published Dick Johnson's 208 page book "The Alps at the Crossroads" in December 1974 to support its quest for an Alpine National Park in Victoria. The first paragraph of that book's introduction sets the scene. Whilst the book is specifically focused on Victoria, it encapsulates the main concerns, goals and objectives of the Green Movement for alpine areas in Australia during the early nineteen-seventies.

"In the 19th Century the alpine region of Victoria was extensively mined for gold and during this period and in all the years following was grazed by cattle. Despite the harmful effects of these activities the country, even thirty years ago, was very much an unroaded wilderness, a vast natural expanse of mountain country with a wonderful feeling of spaciousness that gave an intense exhilaration to those visitors privileged to pass through it. But the destruction of the 1939 fires and the post-war industrial boom brought a need for timber which could only be obtained from the mountains, and the roading and logging of the great wilderness commenced."

The Introduction then notes that only a few tiny pockets of unroaded country are left and that "roads bring trailbikes and four wheel drive vehicles, litter and damage and the path of the thoughtless vandal". Concern is expressed that "the absence of a national park means that no-one has the specific responsibility to consider the conservation of the natural scenery, the natural environment, or the more intangible but no less important features of the high country – its solitude and its silence." At that time (1974) the State Electricity Commission, the Lands Department, the Soil Conservation Authority and the Forests Commission all had responsibilities in the alpine region. "Divided control, disunified objectives and the failure to include socio-environmental considerations in the making of decisions" were marked features of alpine management then.

With the coming of the white man, the previous mosaic of burnt and unburnt country throughout the alpine region, which had allowed the mountain forests to sustain themselves through natural wildfire on a limited scale, was replaced by intense fires, deliberately lit at inappropriate times (such as mid-summer) and in inappropriate places. "Gradually, the grassland understorey turned to dense thickets of scrub, creating an environment more prone to fire and less subject to self regulation by natural mechanisms." A good example of this scrub is on the north-west bank of the Snowy River uphill from the suspension bridge near Illawong Lodge.

Dick Johnson does draw attention (on page 143 of "The Alps at the Crossroads") to the valuable contributions to the Community made by the mountain cattlemen and their huts. "The cattlemen also service the high country. Their huts, open to all, have saved the life of many a traveller and the cattlemen themselves have assisted in many search and rescue operations in the mountains over the years. The cattleman is almost a resident – he knows the area, he lives in it for lengthy periods and he is hardened to its harsh conditions. He is a source of information, a keen observer of men and his own hopes for the mountains are not so very far removed from those of most conservationists. This is the paradox of the cattlemen; the cattle are a tax upon the environment, their masters a benefit to it."

From the skiers' point of view, the more significant of the Green Movement's conclusions and recommendations for alpine areas, as contained in "The Alps at the Crossroads", can be summarized as follows:

Recommendations for alpine areas

|

To justify the proposed ban on building additional huts within the proposed national park, the prevailing view of the Green Movement was that ski tourers should overnight in tents or snow caves. The risk to ski tourers of asphyxiation due to lack of oxygen, caused by burial of their tents and/or snow caves by an overnight heavy dump of snow, was not understood at that time (1974). For further details, please see the section headed "Death of Four Snowboarders in their Snow Cave" at the conclusion of this installment.

The Alpine National Park, covering the alps in North-Eastern Victoria, was established in the late 1970's. The three organizations that supported and participated in all stages of the preparation of Dick Johnson's book were:-

- The Victorian National Parks Association;

- The Federation of Victorian Walking Clubs; and

- The Save Our Bushlands Action Committee.

SURVIVAL AND MAINTAINANCE OF THE MOUNTAIN HUTS

The cancellation of the Kosciuszko alpine grazing leases in the 1960's, with the departure of the mountain cattlemen, coincided with the marked increase in the numbers of bushwalkers and skiers using the mountain huts. After the snow leases served by Mawsons Hut were cancelled in 1963, the Exclusive Squirrel Ski Touring Club commenced looking after that hut. However, few of the other huts were being maintained until the Kosciuszko Huts Association (KHA) was founded in 1970. Since then over forty groups, clubs and individuals have volunteered to maintain the Kosciuszko huts through the KHA. Work has included everything from general cleaning, collecting fallen branches from the forest floor and cutting dead timber for firewood, to major structural repairs.

The NSW Government compulsorily acquired the AAC managed Lake Albina lodge in 1969. Sections of the conservation movement queried the very existence of huts above the snowline. Some of the huts were in a poor condition before their maintenance was taken over by caretaker groups and the KHA. One such hut was Moulds Hut located near Spencers Peak, about 9km ENE of Mt Jagungal. Although the exterior renovated hut was painted in 'park brown', aluminium sheeting had been used internally to seal the hut against draughts and moisture ingress. In February 1976 the hut was deliberately set on fire and destroyed.

Alpine hut, a ski touring hut extensively used in the 1940's and early 1950's (please see the Second Installment of this series), was allowed to burn down in 1979 and Constances Hut was destroyed by fire in 1984. Rawsons Hut, whose condition in 1982 was assessed as fair internally and structurally sound, sympathetically located in a very sheltered position beside the headwaters of the Snowy River at the northern end of Etheridge Range, was demolished.

Acting on the adopted Plan of Management for the Kosciuszko National Park, Lake Albina Lodge which provided a base for Main Range skiing (Photo No. 39), was burnt down in March 1983 by Park workmen. The Park Helicopter removed metal (such as roofing tiles) that had survived the fire. What was in 1969, the best equipped and best managed Main Range lodge, had been allowed to degenerate into an alpine slum through lack of routine maintenance. Following the demolition of Lake Albina Lodge, the Illawong Ski Tourers seemed to be the next in line for demolition, particularly when advised by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service that "The position is that occupation on a caretaker basis by the Illawong Ski Tourers of the Illawong Lodge has been approved until 31 December, 1985, but not beyond and no negotiations concerning tenure beyond that date are in progress or will be entertained."

Prior to 1985, part of the boundary of the Kosciuszko National Park was located about 5km east of Mount Jagungal on the crest of the Munyang Range at about 1700 metres elevation. The Snowy Plains, with clumps of trees separated by broad grassed areas, exist to the east of this former boundary and slope gently down to the Gungarlin River at 1400m elevation some 8km further to the east. This ideal ski touring land was privately owned freehold land zoned Rural 7c and was mostly used for stock grazing from Spring to Autumn each year. Portions 35 and 36 Parish of Gungarlin were owned by Bryan Haig, a keen cross-country skier and a past president of the ACT Ski Council, who lived on the property for much of the year and hosted other keen ski tourers in his home, which was called Bogong Lodge (Photo No. 40).

The AAC and some other ski clubs were most interested in constructing a few small huts on Block 36 for ski touring and bushwalking purposes. In December 1984 the retiring NSW Minister for Planning and Environment, Mr Terry Sheahan, approved the compulsory resumption of Bryan Haig's Block 36 by the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) to allow its incorporation into the Kosciuszko National Park. This action was confirmed (by telegram dated 18 January 1985) by the incoming Minister, Mr Bob Carr.

Minister dated 21 January 1985) that Bogong Lodge, Bryan Haig's home overlooking the Snowy Plains, be retained as a shelter for ski tourers, to be administered by a committee of management consisting of ski clubs and governmental agencies (such as the NPWS and the NSW Department of Planning and Environment) with an annual rental being paid to the NSW State Government and with Bryan Haig initially acting as caretaker,.

All the events summarized in this section of the Eighth Installment, represented the end of the 1950 dream of the Ski Tourers' Association that had driven it to establish a chain of huts across the NSW Alps. Henceforth, it was apparent that the Australian Alpine Club could only build huts in established ski villages, because even dwellings on freehold land were no longer safe from compulsory acquisition and subsequent demolition.

WATER FROM THE ROCK AT DINNER PLAIN

Building on the previous experience from the Perisher Ground Water Investigation in the 1970's, detailed geological and hydrogeological investigations of the Dinner Plain area were performed by Warren Peck of Golder Associates, in November 1981. The aim was to obtain.subsurface information as to the possible existence of a groundwater resource and to obtain data for the foundation design of the proposed ski village at Dinner Plain on the crest of the Great Dividing Range at 1570m above sea-level.

Most of the 231 hectare freehold property is underlain by basalt of Tertiary age, with a total thickness in excess of 40 metres. It was found that the nature of the vegetation cover gave a good indication of the depth to fresh basalt rock. Grassy areas that are relatively free of trees had fresh basalt rock at depths of one to two metres, whilst treed areas were generally underlain by soil and decomposed rock down to about 8m depth.

It was established that the basalt within the property stores a large volume of water equivalent to about two years requirements for the proposed village. The groundwater supplies are continuously being replenished by infiltration into the ground by rain plus water from the melting winter snow cover and by seepage from the higher ground to the west with a total catchment area of about 500 hectares (that includes the "Weeping Rock" visible from the Alpine Road).

Excellent quality drinking water was pumped from a 75mm diameter investigation bore at the consistent rate of 2.44 litres/second for over 10 hours, with a groundwater draw-down of the water-level inside the bore of only 2.4m.

The samples taken of the water pumped from the Dinner Plain bore, when laboratory tested for water quality, had a total dissolved solids of 24.5 parts per million and were the purest drinking water samples ever tested from a water bore in Victoria. For comparison purposes, the best bore water sampled from elsewhere in the Great Dividing Range in Victoria had 100 parts per million total dissolved solids and a typical bore water sample from basalt near the crest of the Great Dividing Range at Allora in Southern Queensland, had 980 parts per million total dissolved solids.

These results clearly indicated that a valuable water resource existed under the Dinner Plain Village, with the capability of supplying the village's entire water supply requirements. The total annual water requirements of the village of 100 megalitres represents less than 2.5% of the average annual precipitation on the 500 hectare catchment. The fact that the period of greatest demand for water immediately precedes and overlaps with the period of maximum infiltration means that the amount of drawdown in the pumped bore would only fluctuate between 4.9 metres at the end of July to 2.0 metres at the end of September.

Two production bores were sited in the mid-1980's, using the results of seismic refraction surveys to locate each bore within areas of intersecting fractures in the basalt rock, since the main groundwater flow is along these fractures. These two bores provide the entire water requirements for the reticulated water supply at Dinner Plain. The actual performance of Dinner Plain's underground water supply was reviewed at the end of 1993 after several years of village operation. The Shire of Omeo maintained detailed records of water quantities and water levels in the two production bores. Each bore had yielded around 4.5 litres per second when pumped and the annual utilization for the year ended 30 June 1993 was 44 megalitres, which is 63 per cent of the capacity of the upper aquifer. The lower aquifer had not been needed at all. When Waterbore No. 1 was pumped continuously for 52 hours in July 1993, it yielded 841,600 litres at an average rate of 4.5 litres per second. The groundwater level at the start of this test was 1.6m below the ground and was only 2.0 metres below the ground at the conclusion of the 52 hours of continuous pumping. Hence there is negligible environmental impact resulting from this water supply system.

DINNER PLAIN ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS STATEMENT

In order to gain an initial feeling for public attitudes to and interest in the Dinner Plain proposal, it was originally advertised by the Ministry for Conservation in early July 1981 in the Melbourne "Sun", "The Age", the Melbourne "Herald", the "Bairnsdale Advertiser" and the "Albury Border Mail". A very detailed Environmental Effects Statement with detailed drawings, was issued in January 1982.

The proposal was to construct a dormitory Alpine Village on part of the 231 hectare property. "The proposed total size is to be 4,000 beds comprising:

- 100 bed Hotel

- 250 Apartments

- 150 Row Houses

- 12 Commercial Lodges / Pensiones

- 20 Club Lodges

- 10 Commercial Sites (Ski Hire, Coffee Shops, etc.)

All of the sites will have the buildings totally designed and built with staging of the village growth, dependent on market forces. The Developers will bear the capital cost of all infrastructure facilities and services. The Shire of Omeo will own all the infrastructure services and facilities and be the authority responsible for the operation and maintenance of same. The costs of this operation and maintenance will be recouped via the normal rating system. The total infrastructure system would be installed prior to development. A bus system will be established to transport skiers to and from Mount Hotham provided by the proponents and the residents."

"The development of skiers' accommodation at the Dinner Plain site has considerable advantages over providing further accommodation at the Mt. Hotham Village. These include ease of car parking, ease of access, ease of providing services, and a protected flat site." Dinner Plain was offering land under a Torrens Title, a security not available in other Australian ski resorts.

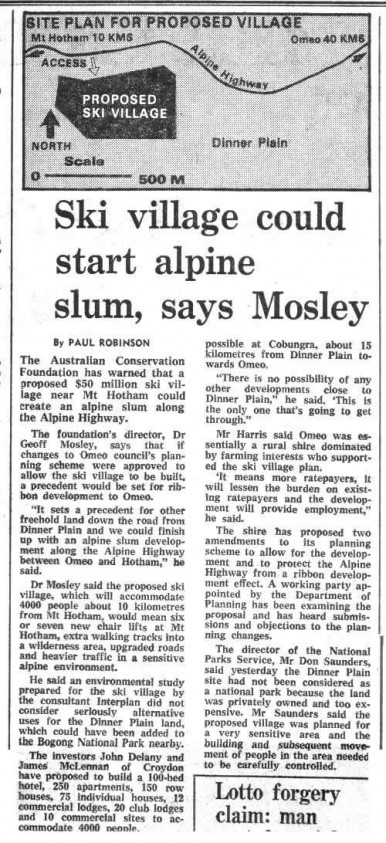

ENVIRONMENTALISTS OPPOSE DINNER PLAIN DEVELOPMENT

"The Age" newspaper of Tuesday 9 March 1982 contained (on its Page 15) a report (see our Photo No. 41) that Dr Geoff Mosley, Director of the Australian Conservation Foundation, condemned the proposed $50 million ski village.

The Conservation Movement then proceeded to make numerous costly planning and administrative challenges against the Dinner Plain Village at the Local Government Level on environmental grounds for almost three years. For example, although the village's proposed water supply "from the rock" would have minimal environmental impact, compared to a conventional design involving a dam on the Victoria River, it was one of the issues that was hotly debated, requiring Warren Peck to attend several hearings to defend the concept of a reticulated water supply obtained from boreholes. The Dinner Plain Development was finally allowed to proceed just prior to Christmas 1984 with construction commencing on village infrastructure in February 1985.

AAC LODGE AT DINNER PLAIN

Once all the challenges and appeals against the proposed Dinner Plain Village had been processed, the AAC was allocated one of the 20 Club Sites in late 1984 and Bryan Linacre was the founding chairman of this new AAC Affiliated Project. The formal board of AAC (Dinner Plain) Co-operative was formed with seven paid-up members who then purchased Dinner Plain Lot 101 in January 1985 using a loan of $10,000 from the AAC Council to provide the deposit for Lot 101.

A site inspection convinced the Board that the new lodge would need a lot of members and, since it is a co-operative, each member could only hold one membership debenture. Additionally, no person under the age of 16 years could be a co-operative member. The co-operative was registered in February 1985, and the cost of an original membership was $3,000 per person. The Board allowed members to pay for their debentures over an 18 month period, and aimed to have as many members as possible prior to the commencement of construction of the lodge. Members were recruited not only by word of mouth among friends and skiing associates, but also by circulating invitations to join to all persons on the waiting lists of the other AAC lodges. For example, the Anton Huette had about 100 persons on its waiting list, of whom 20 joined along with their spouses, children and friends. Members of the other AAC affiliated lodges were of great assistance by talking to prospective members and encouraging them to join. They included Leon Smith, Gordon McDermott, Bob Marshall and Liz Lewis.

Peter McIntyre and Associates had been appointed Architects to design a lodge that included a large lounge containing a large open fireplace, an efficient large double-kitchen and 8 large bedrooms, each with an ensuite and two beds. Construction commenced following the end of the 1986 ski season (Photo No. 42), by which time nearly 250 persons had joined AAC Dinner Plain.

The AAC's Dinner Plain Lodge was opened by Noel Carter, the then AAC President, on 18 June 1987. During his time serving on the Anton Huette Committee, Noel had worked hard on trans-AAC initiatives, such as the "Ski Touring in Australia" book. He had invited Yutta (Charles Anton's widow) to attend an Annual General Meeting of the Anton Huette, so that she could see for herself how the goals of Charles Anton still guided the AAC some twenty years after Charles' passing. In Photo No. 43, Noel is holding the Charles Anton commemorative plaque that he presented to the AAC Dinner Plain Lodge during the opening ceremony. Noel spoke very eloquently about how the building of the AAC Dinner Plain Lodge was a further step towards the attainment of the AAC goals, first enunciated by Charles Anton in the 1950's

In June 1988 the adjoining Lot 100 became available and AAC Dinner Plain purchased this block, so as to provide room for future expansion of the lodge, by selling a further 25 memberships. The total membership of the lodge is 300. The lodge has operated well and has a good occupancy rate during the ski season, when many of the occupants use the bus service to access the Mt. Hotham ski runs. Its location above the snowline (Photo No.45) makes it an ideal venue for ski touring.

The 11km separation between the Dinner Plain Lodge and Anton Huette in the Mt. Hotham Resort, provides a very pleasant ski touring trip with the bus service between the two resorts being available for those who do not wish to do the round trip on skis. Other cross-country ski trails at both resorts provide many other opportunities for the ski tourer.

The main goal of the Ski Tourers Association (which became the AAC) was to establish touring shelters across the Australian Alps. Located at Dinner Plain is the only AAC Lodge that is one day's comfortable ski travel from another AAC Lodge (Anton Huette at Mt. Hotham).

DEATH OF FOUR SNOWBOARDERS IN A SNOW CAVE

The relevance of this event to Australia's Ski Heritage is that it is a sad demonstration of the value of huts above the snowline, not only from the aspect of providing safe shelter, but also their value in simplifying the location of overdue cross-country travelers in the snowfields. Unfortunately, snow caves and tents can become death traps if heavy snowfalls occur and/or large snowdrifts develop in windy conditions overnight.

On Saturday morning 7 August 1999, four adult male snowboarders carrying heavy packs departed the top station of the Thredbo chairlift bound for the area between the Racecourse Gully and Lake Albina, a distance of 10km, where they planned to dig a snow cave and snowboard the nearby slopes. They had left a map, on which their planned route was marked, plus their planned schedule, with a close relative, who was asked to phone the Jindabyne police should they have not returned by Monday night 9 August.

The weather forecast issued at 5.30am for that Saturday, was for a fine and mostly sunny day with moderate to fresh northerly winds and nil probability of snow overnight. The forecast did warn of deteriorating weather from Sunday into Monday. However, the storm developed soon after the four snowboarders had left Thredbo and by midnight Saturday night, the Kosciuszko Main Range was subjected to gale force winds and driving snow.

A group of scouts and adult leaders had camped that day about mid-way between Thredbo and Mt. Kosciuszko, just over a kilometer from the snowboarders, but unaware of the snowboarders' presence. One of the leaders of the scout group had pitched a tent whilst the others excavated a snow cave.

After their evening meal the scouts had retired to their sleeping quarters. The tent occupant awoke just after midnight to find his tent buried under masses of drifting snow. After clearing snow from around the tent's entrance, he went over to the snow cave and unblocked its entrance, so as to maintain the air flow to its occupants. It was snowing so heavily that he had to repeat this clearing of the tent and snow cave entrances two more times during the night.

When the four snowboarders had not returned to Thredbo by 9pm Monday, the Jindabyne Police were contacted. The Police verified that the snowboarders' car was still parked at Thredbo and, after an overnight check of the local bars, hotels and lodges in Thredbo, a full search commenced at 7am Tuesday morning. The search continued every day for nearly three weeks and found no trace of the missing men, despite covering 300 square kilometers and involving up to forty searchers with oversnow vehicles and aircraft.

The possibility that they had been buried under a massive cornice avalanche that had occurred off the south-eastern slopes of the Kosciuszko Summit Ridge was tested by digging with large machines. Special airborne thermal sensing gear found no trace of human warmth in the bush or under the snow.

By the end of August the reluctant conclusion was drawn that the missing four men were deceased. Occasional air searches were carried out during the Spring thaw. On Tuesday 16 November, the crew of a naval helicopter spotted a black hole in the side of a snowdrift and landed to investigate. Ski poles were protruding through the snow beside the black hole, which was the entrance to a snow cave. The bodies of all four missing men were found inside the snow cave, which had not collapsed. A stove had been used but autopsies showed that carbon monoxide poisoning had not occurred. No blood alcohol was detected in any of the four deceased men. The pathology report concluded the four deaths were the result of accidental suffocation, possibly combined with hypothermia in two of the four cases.

John Abernathy (NSW Coroner) commented, "I can only say that it would be prudent for snow cavers to always ensure that some type of aperture to the open air is kept, even if this means maintaining a 'watch' throughout the night."

Dr Peter Hackett, then President of the International Society for Mountain Medicine, quoted a 2001 disaster in Nepal when the dean of the Washington University medical school, his family and all their Sherpas were suffocated in their tents. "They suffocated in a huge snow storm that buried their tents. No avalanche, just heavy snow". Dr Hackett also drew attention to the significant risk of carbon monoxide poisoning in tents and snow caves from using camping stoves. The obvious conclusion is that mountain huts are much safer places than snow caves and tents (particularly those tents made entirely of water-proofed, impervious fabric).

SEARCH IMPLICATIONS – TENTS AND SNOW CAVES

One of the most concerning aspects of the suffocation of the four snowboarders in their snow cave, is the virtual impossibility of finding snow caves and tents that have been buried under the snow, unless their locations are already known to an accuracy of better than +/- 100 metres.

Sergeant Warren Denham of Jindabyne police, who was the field leader of the search for the four snowboarders, is very certain that he and other teams passed directly over the site, or very close by, several times during the first few days of the search. So much snow must have accumulated that all sign of the snow cave was buried, including the ski poles standing alongside its entrance.

Mountain huts containing logbooks, in which all parties record their travels, are the best means of minimizing the size of the area to be searched in order to locate a missing person or a missing group.

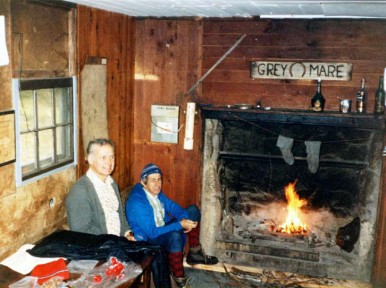

Two invaluable survival-enhancing features can be seen in Photo No. 46, taken in 1987 in the Grey Mare Hut in the Kosciuszko National Park: -

Firstly there is a fire burning in the fireplace to dry wet clothing (with supplies of dry firewood stored in a "lean-to" against one external wall of the hut) and, secondly, a logbook can be seen prominently displayed on the wall to the left of the mantelpiece. During any search in this area, the logbook would be the first thing to be consulted by searchers, should the missing skiers/hikers be not physically present in the hut when the search party arrived.

There also is a map mounted on the wall beside the window, should a touring group have accidentally damaged, or lost, their map of the area.

Even basic cattlemen's huts, like Horsehair Hut (Photo No. 47), provide shelter from the elements, plus a fireplace and the opportunity to dry wet clothing and equipment.